Come Drink With Me (King Hu, 1966)

October 1, 2010

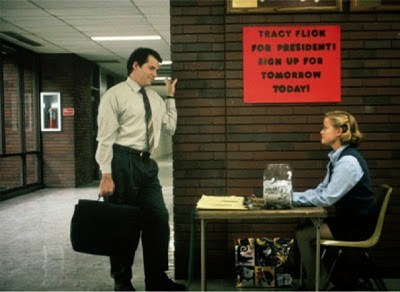

Election (Alexander Payne, 1999)

October 1, 2010

Benjamin Ross

Benjamin Ross considers that he was, when younger, a movie fanatic. He cites classical literature such as Dickens, Conrad, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy as influences for his work, which could account for the classical feel of his first film, The Young Poisoner’s Handbook, as well as other, more contemporary writers like Kesey, Tom Wolfe and Kerouac. He cites influential directors like Scorsese, Kubrick, Milos Forman, Lindsay Anderson and Emir Kusturica which he met in film school, as well as more mainstream work like the Tarzan movies and several different other genres. With the realization that most of his references were American came the desire to transcend those limitations: “I had gone to New York thinking that somehow I had to make myself American because all my influences were American. In fact, when I got there, I found myself thinking about home and who I was. The experience of being dislocated somehow made me realize what I had to write about, which was what I knew”. This is the dilemma of every cinematography on Earth, living in the shadow of the imperial Hollywood machine. Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino’s elaboration of a Third World cinema is based on this desire to escape the overbearing influence of American cinema.

Like Terence Davies, Benjamin Ross allows a certain intuition in the elaboration of his work:

To be honest, I never look at subject matter and say, ‘Oh, that interests me because of its theme.’ It’s a purely instinctive thing for me, more like, ‘Where do I want to put myself for what’s likely to be the next two, three, possibly four years of my life?’

Ross and his co-writer were given money by the British screen to work on the screenplay of The Young Poisoner’s Handbook which took two years. He recalls being prepared for the shoot, going so far as to entirely storyboard the movie:

I try to know everything and then improvise. Then it all changes and you have to try to be open to that. That’s the challenge, I suppose.

On his shooting style, he admits being a minimalist when it comes to the specifics of the shoot:

I like to keep things terribly technical. I’m very happy if my DP says, ‘A little to the right. A little faster.’ Very simple things.

Contrary to the shooting, which Ross finds difficult, he loves the editing process:

That’s the part I can enjoy, because you’ve got your material and then you’re really making the picture. You can make decisions and if it’s not right, you can undo it and try something else.

And, that’s exactly what Ross did when, after a screening at Cannes, he realized that the picture needed fine-tuning and raised the necessary £50,000 to go back into the editing room and cut down his film. Ross also seems knowledgeable and specific about the look of his movie, a quality usually absent from first-time directors:

We wanted [the film] to be like a progression of English film stock so that it would have historicity. It goes from the Ealing Studios look of the late 1950s, through to A Clockwork Orange, bleached Eastman, of the early seventies.

Ross’s first brush with production didn’t go quite well, and he admits that his student film was a disaster:

[…] It was a very good learning experience. I used actors who were not good. All the things that can go wrong with a production, over which you have no control because you have no money, went wrong.

On The Young Poisoner’s Handbook, the complicated financing, a European co-production between England, a French co-producer, and a German producer, brought some problems with it. The German money, from public funds, meant some of the film had to be shot in Germany with a German-speaking crew:

We had a very tight schedule and it was quite hard switching to German, because we had a largely German crew. […] Shooting is difficult, but it was more difficult in Germany because of the language difference and because the crew really weren’t up to speed. It was a cultural chasm, really.

Contrary to the other three filmmakers reviewed here, Ross’s first effort was well received and did well: [The film] got critically lauded everywhere and won a lot of prizes. It has enabled me to at least establish my name as a filmmaker.” Ross’ sophomore effort, RKO 281 for the American channel HBO, depicts the battle of Orson Welles to have Citizen Kane distributed. Although not as powerfully inventive as The Young Poisoner’s Handbook, it is nonetheless an interesting entry in Ross’ growing filmography.

James Mangold, director of Heavy, trying to comprehend the term “independent”, declares that “independent film contains a populist rhetoric, against the system, against the grain”. What distinguishes these four filmmaker’s oeuvre is its departure from the norm, whether the Hollywood model or the European art-house aesthetic. These directors somehow seem to navigate in-between these tendencies. But can they really be considered independent? “Some people are groping for definitions of independent and they just don’t exist, declares Richard Linklater in his interview. I would say independent is private financing, and having absolutely no interference. But like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, by the time such a definition is elaborated, hasn’t the elusive independent term morphed into something else?

Bibliography

FALSETTO, M.: Personal Visions: Conversations with Contemporary Film Directors, Silman-James Press, Los Angeles, California, 2000.

LEVY, E.: Cinema of Outsiders, New York University Press, New York, 1999.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015