Come Drink With Me (King Hu, 1966)

October 1, 2010

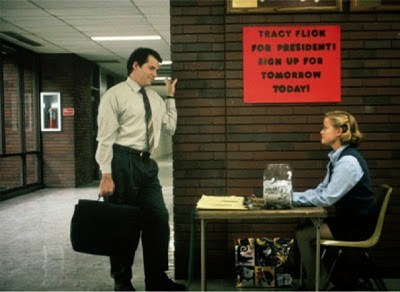

Election (Alexander Payne, 1999)

October 1, 2010

Richard Linklater

Richard Linklater is the quintessential independent American filmmaker. Kevin Smith cites him as an influence for his first film, Clerks. Originally from Texas, he was able to work, until now, both as an independent filmmaker and as a Hollywood director. His first feature, Slacker, was seminal in that it seemed to come at a time of generational transition. To him, life in his native town of Huntsville, Texas was culturally disadvantageous although, since his parents were educated, his dad would take him to “museums, movies, and things like that”. He cites 2001, A Space Odyssey as “having a really profound effect”. “That’s a tribute to Kubrick’s genius, I guess, that it could communicate so clearly on so many levels,” continues the filmmaker. He also cites David Lynch and Martin Scorsese as influences: “[…] I saw Raging Bull, which became another touchtone for me. […] It was like ‘Oh my God! Film can be that?’” Further through the interview, he names French New Wave director—and a personal favourite of mine—Eric Rohmer as an inspiration for the style of Before Sunrise. Rohmer’s style is renowned for being verbose but, in opposition of Rohmer’s characters who seem much taken by themselves and egocentric, Linklater’s characters in Before Sunrise seem genuinely disposed to communicating with each other.

Linklater talks about the development towards Slacker as a journey, beginning with his Super8 experiments, rather than as a singular experience. The writing was additive; the process itself was short, but the accumulation of material took a long time: “For five or six years, I’d been keeping notebooks of ideas, weird little things, dialogue or whatever. In one twenty-four-hour period, in spring 1989, I sat down and wrote the entire script.” The “narrative experiment” is about communication and forces the spectator to always inhabit the present of the story and not be distracted by any previous history: “There’s a certain pissed off, on the verge of anarchy quality. […] [The characters] had no names, they had no desires outside what was going on in their head. […] It’s almost like channel surfing.” As well, in the post-production stage, editing was crucial to keeping the film documentary aspects. Linklater persists in using long takes as part of the film’s style: “It’s just the way it felt natural to tell that story. […] I wanted it to seem unmanipulated and real, and the more cuts you make, the more the audience, on some level, is aware of being manipulated. Of course, sometimes I had to cut, and it felt like some kind of moral violation. When I started cutting, I didn’t like doing it at all. Every cut was a big deal.” Linklater here seems to adhere to the famous Robert Bresson quote: “Every cut is a moral decision.”

When asked if the shoot was difficult, Linklater doesn’t seem to regret Slacker’s limited budget: “We shot in thirty-five days over a two-month period and a lot of those were half-days. That’s pretty fast, especially for a no-budget film.” A lot of artists talk about the sophomore curse, that fact that critics often put great expectations on sophomore efforts. Linklater recalls that invisible pressure on Dazed and Confused: “Slacker had got some recognition, so you feel the scrutiny a little more intensely. They’re really judging you on that next film. It’s almost like everyone but your closest friends wants you to fail. They ask, ‘Are you just someone who got lucky, or are you a real filmmaker? Do you have more than one movie in you?’” This intangible curse has prevented several promising filmmakers from ever putting out a second effort. Most independent filmmakers talk of the difficulty of financing their second feature. Financing aside, distribution is also a recurring theme. Dazed and Confused wasn’t really supported by its studio, Universal: “I got a modest release, like 183 theatres. Universal was never very excited about it and it got passed off to a smaller distributor they had recently partnered with, Grammercy.” The emerging independent filmmaker, Dylan Kidd, who amazed with his first film, Roger Dodger, was confronted with the same reality of distribution when his sophomore effort, P.S., was released to video after a limited release in New York. The same considerations plagued Benjamin Ross and he expressed it as catharsis in RKO 281, which relates the battle to make Citizen Kane.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015