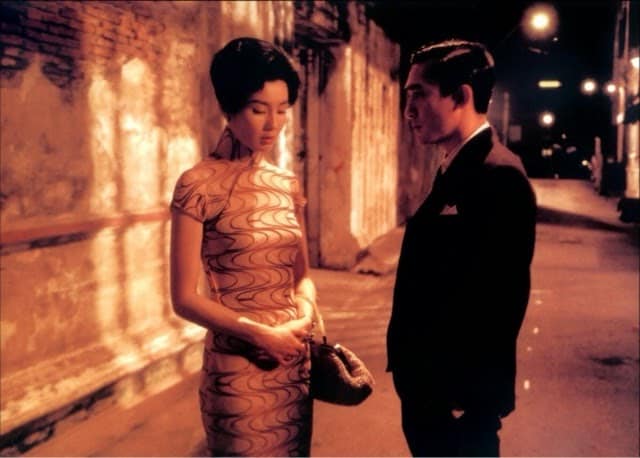

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

September 28, 2010

Coming Home: Melodrama and social change

September 28, 2010eXistenZ: The abject nature of the simulacrum

In eXistenZ, the abject object is virtual. To Allegra Gellar, “eXistenZ is not just a game” but a whole other world preferable to the real one. In the first scene, in the design of the technological toys used like the game pod or the kid’s controller, we see that this future world has an organic-based technology, almost a descendant of Max Renn’s symbiosis with technology in Videodrome. When at Kiri Vinokur’s house, Vinokur dissects Allegra’s pod to fix its wiring and Ted remarks that it “looks like an animal in there.

Allegra Gellar is considered an abject figure throughout the movie because she’s a game designer and creates these virtual realities where people can escape to. In the testing scene at the beginning of the movie, she is shot with a weapon made of flesh and bone, a reflexion of the realists’ way of thinking and rejection of modernity. After their getaway following the shooting, Ted extracts the projectile from Allegra’s shoulder and discovers that it’s a tooth. In their hotel room, Allegra discovers Ted had never been implanted with a bio-port, an input-output port linking the body to the outside world, he tells her ‘I have this phobia about getting my body penetrated’. As Julia Kristeva articulated earlier, it is this whole relationship I/Other, Inside/Outside that is problematic and leads to the rejection of the abject object that menaces the subject’s identity. But since Allegra needs another gamer to verify that her game is still intact, they have a garage man install one for him. Ted will refuse it, hesitant in desecrating his body that way but Allegra will convince him to do it. Later, when Ted sees a two-headed creature walking on their car, Allegra identifies it for him: ‘a mutated amphibian, she says. A sign of our times.’ Technology has not only bridged man’s limits and corrupted him but has also laid waste to nature, degrading it into a random pairing of its old constituents. Then, in the game, Ted is served that creature when he asks for the special at the Chinese restaurant as he was instructed to. To ingurgitate this abomination will turn both Ted and Allegra’s stomachs. We have the same effect when Allegra jacks into the diseased port, the feeling of unease that signifies the invasion of the body from the outside. Yevgeny Nourish, the character that sent them to the Chinese restaurant, is stabbed by Allegra and only has the time to yell out, as if rejecting the abject object, ‘Death to the demoness!’

Kristeva writes in her book, ‘There is in abjection one of those violent and obscure revolts of being against what threatens him and seems to come from an outside or an inside exorbitant, thrown to the side of the possible, of the tolerable, of the thinkable.’ From the beginning of the movie, it is evident that Allegra, substituted for the real game designer Yevgeny Nourish, is the abject object, from the young assassin yelling out ‘Death to the demoness Allegra Gellar’ to the battle scene where the game pod is destroyed, the realists goal is to destroy this artificial reality that cause the gamer to numb himself to reality. Their violence is only extreme because they feel threatened themselves. They endeavour to push back technology to the limits of the body, effectively protecting their interior against the exterior world. In the end, by killing Yevgeny Nourish and his assistant, Ted and Allegra accomplish their goal, destroying the symbol of their abject object. But as the gamer asks them, is it real? Have they sacrificed the sanctity of reality to forever be lost in their abjection?

In Videodrome as in eXistenZ, Cronenberg explores the connections between man and media, his relationship to it. If in Videodrome, Max becomes the technological medium, that it takes his place, cannibalizing him, superimposing itself unto him, in eXistenZ, the medium’s danger comes from the fact that, being connected to it (in this case a virtual reality game), it becomes impossible to tell where the medium’s effect on the individual start and where they stop. But what predominates in those two films is the perverse nature of self, the crooked tangent the individual follows when exposed to science and its critical views of man’s connections to technology. Therein lies the horror, that by abandoning the natural individual, science corrupts the defined order which can only lead to a violent abnegation of modern man, a return to the primitive and violent. Julia Kristeva mentions this rejection in her book, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection; to her, once the individual is in a state of crisis, he must reject the abject object with which he has a constant relationship. In Videodrome, this rejection is that of Max, refusing to accept the creature he has become, signified by Cronenberg’s critically symbolic depiction of Max’s transformation. In eXistenZ, it is diagetic, signified by the subversive guerrilla-like group opposed to the proliferation of the eXistenZ technology. Does Max become the precursor to a new man? Are Ted and Allegra representative of a generalized social malaise? The key to Cronenberg’s discourse could well be the ambiguity of the two movies. Where emotion meets intellectuality, isn’t that possibly where we’ll find the filmmaker’s truth?

Bibliography

BAUDRILLARD, J.: Simulacres et simulations, Galilée, 1981.

FREUD, Sigmund : The ego and the id, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1960, 1962.

KRISTEVA, J. : Pouvoirs de l’horreur : Essai sur l’abjection, Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 1980.

LECLERC, S. : La Science-fiction au cinéma, Notes de cours, Université du Québec a Montréal, Hiver 2003.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015