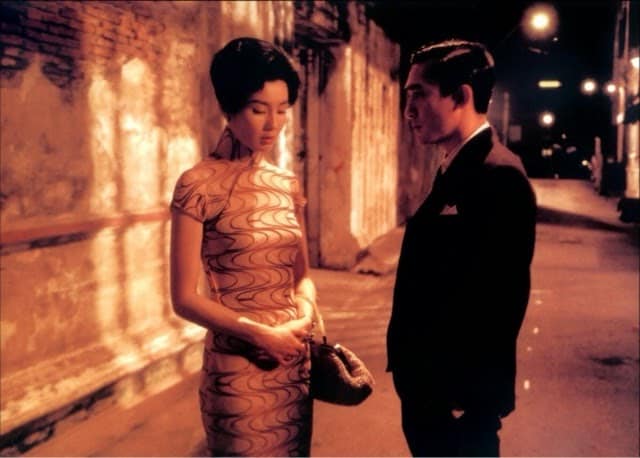

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

September 28, 2010

Coming Home: Melodrama and social change

September 28, 2010David Cronenberg’s filmography is recognized as a strange and visceral experience. It speaks, to employ psychoanalytic terms, directly to our id, that part of us that is irrational, at its worst bringing to the surface an illogical fear and, at its mildest, a discomfort in the spectator. A reoccurring theme in the filmmaker’s oeuvre is that of man and of his relationship with science and technology. Does Cronenberg create a modern or postmodern look on the modern man? Is it critical or simply narrative? How does Videodrome link to eXistenZ? Do they share a common discourse?

I will explore the duality of Cronenberg’s works, as a statement on man’s curiosity (science’s principal driving force) and an open window to the unknown and as a refusal of that undefined and horrific future reality, by concentrating on Videodrome and eXistenZ, two of his films linked by his unique style and vision but part of two different periods of the filmmaker’s career.

Videodrome: Long Live the New Flesh!

In Videodrome, Cronenberg explores the relationship of modern man to the television screen. Max Renn, a television producer, whose area of expertise is violent and sexually explicit programs, is confronted to Videodrome, a snuff television program whose realism is striking. From the opening shot, Max’s dependence on the television screen is apparent: a television screen turns on, showing a commercial of Civic TV, “the one you go to bed with”, with the drawing of a man in bed, a television on his legs. In an ironic depiction of the modern importance of the television, Cronenberg replaces the desire for a companion, a better half, by the desire for television. Human interaction is therefore relegated in favour of man’s relationship to technology. His secretary then appears on the screen, trying to wake him, further signifying Max’s isolation.

Later, on the Rena King Show, a television show, Max will be reprimanded for the violent and sexual contents of his television programs to which he will respond that he’s doing a public service by creating a safe and harmless outlet for his viewers’ frustrations. To him, his shows are cathartic, with no consequence on the state of mind of his audience; it cannot incite, only express the repressed. “We live in overstimulated times,” states Nikki Brand following Max’s declaration, as to criticize his kind of television, but she has to admit that she can’t help but being a part of that overstimulated world. The first time Max sees Nikki on the show, we only see her image through a monitor. In the same way, Dr. Brian O’Blivion, a character who’s defined only through his television image, says that he refuses to appear on television physically, choosing instead to do it through a television (we can imagine the viewers watching the image of an image of Dr. O’blivion). In a process of mise en abîme by Cronenberg, the television screen refers to itself.

Like Max, Nikki is a producer and consumer of media content, working in a radio station on The Emotional Rescue Show, giving out advice to her listeners. Her position here is ironic since her penchants for sadomasochistic behaviour will be revealed. At Max’s apartment, looking at his video cassettes, she asks him if he has any pornos to put her in the mood. When she finds Videodrome and asks him what it is, she seems to be interested in the violent content it carries. Max tries to dissuade her by telling her “it ain’t exactly sex”, to which she replies, “who says?” Sigmund Freud, in his explorations of the psyche, thought that the dynamic relationships within the human mind are subject to the influence of two types of instincts:

“[…] we have to distinguish two classes of instincts, one of which, the sexual instincts or Eros, is by far the most conspicuous and accessible to study. […] The second class of instincts (the death instinct) was not so easy to point to; in the end we came to recognize sadism as its representative.”

Guided by her pleasure principle, as defined by Sigmund Freud as the constant desire for pleasure, Nikki sublimates the energies of her death instincts into eroticism, using the television as a focal point for her neurosis, as catharsis as Max had stated previously. Watching Videodrome, Nikki visibly likes it. She asks Max to cut her on the shoulder, showing him the panoply of cuts she has incurred from past lovers or maybe self-inflicted. When they sleep together, it’s under the watchful eye of the television lens, showing Videodrome. Later, when warned by Max not to go visit the Videodrome set in Pittsburg, Nikki, led by her pleasure principle, will answer that it’s “sounds like a challenge. A prisoner of her own desire, she follows her sublimated death instincts to her actual death, immortalized in Videodrome.

Dr. O’Blivion is characterized through television. To meet him, Max goes to the Cathode-Ray Mission, a reference to the Cathode-Ray Tube (CRT) that projects the image on the television screen. The mission, dedicated to helping the destitute homeless of the city, on top of feeding them, offers them a television. One of the homeless, staring at his screen, turns to smile at Max and goes back to his television. Cronenberg is close here to the opinion Jean Baudrillard has of the media:

“Is dissocialized, or virtually asocial one who is under-exposed to the Medias.”

The point of exposing the homeless to the television is to re-socialize them, make them part of this modern consumer society that is contingent on the television to define itself. Max then meets Bianca O’Blivion, who further characterizes her father as a disincarnated spirit, saying she’s “her father’s screen”, observing and acting for him, projecting his message to the world from beyond the grave. It seems important that Dr. O’Blivion is dead but still manages to influence his world through his simulacrum, a television image infused with his personality, his identity, a means of communication in use since before his death. He succeeds in warding off his total destruction, the oblivion to which his name seems to point to. However, in doing so, he becomes incapable of human interaction, a pure product of the Cathode-Ray Tube. Like his daughter reveals, “the monologue is my father’s preferred mode of discourse”. Technology here isolates man, his body submitted to the totalitarian control of technological toys, exposing Cronenberg’s postmodern discourse running through Videodrome.

From that discourse emerges the dangers of dehumanization that such a relationship with technology entails. For Frederic Jameson, the television and cinema spaces are unattainable, unless there is a medium or a transformation of our bodies, with the growth of a new organ, for example. For O’Blivion, the television is an extension of the human body, “the retina of the mind’s exe”. Max is confronted to such a transformation when he watches the tape Bianca O’Blivion gives him of her father, and the Videodrome tumor triggers a hallucination. Max imagines that the wound on his stomach opens up, gaping, pulsating, and shivers for the gun he’s holding. By inserting the gun, he’s in effect penetrating himself, violating the limits of the body, with his gun, a phallic figure, through this vagina-like hole in his stomach. He’s trapped in the dynamic exchanges of Eros (the hole which points to femininity) and Thanatos (the gun which represents essentially a phallus) he instituted with Nikki earlier. Losing his gun inside himself shows that he’s losing control over his mind and body, as does his manipulation at the hands of Harlan and Barry Convex later in the film. His meeting with Barry Convex is also telling. After learning that Barry is responsible for Videodrome, Max is taught that the reason Videodrome is violent is that humans are more receptive to violent and sexual titillation. Under the guise of a carrier snuff program, Videodrome could therefore be “beamed” into television sets and “infect” the whole populace. If, as Masha had told Max earlier, Videodrome is dangerous because it has a philosophy, a message, then that message is being carried out into the world by the television’s rays, the rays being to the medium what the written word is to literature. A spectator exposed to those rays is irradiated with this message; it pierces through the limits of his body into him and provokes the transformation that’s, to this point, afflicting Max. Julia Kristeva says about the breaching of the limits:

“[…] the ambiguous opposition Me/Them, Inside/Outside — a vigorous opposition but permeable, violent but uncertain — of the contents ‘normally’ unconscious in the neurotic therefore becomes explicit or conscious in discourses and borderline behaviours.”

When he wakes up after hallucinating a session of sadomasochism between him and Nikki, transforming into Masha, whom he whips through the television, he’s horrified to find Masha’s lifeless whipped body next to him on the bed. Kristeva thinks, “the cadaver (cadere, to fall), what has irreversibly fallen, dark and dead, upsets more violently the idea of the one who is confronted to it, like a fragile and fallacious fluke”. The proximity of the dead body affects Max, and he calls Harlan to verify its presence in his bed.

In the following scene, at the lab, Barry and Harlan reveal to Max that they set him up to be controlled by Videodrome; the video signal is another element of the totalitarian arsenal, like propaganda, another measure of control. All Max needs now is to be “programmed”, as Bianca O’Blivion will remark later, to be given a purpose by the totalitarian regime he’s being controlled by. Barry takes out a video cassette which pulsates just as Max’s gaping vagina-like opening waits for the imminent intrusion, excited; the absorption of the message made literal. Penetrated by the new message, Max tries to take it out, but he finds his gun instead. A voice-over tells him to kill his partners, which he does, and sends him out to eliminate Bianca O’Blivion. Cornering her inside a booth, he opens the curtains to reveal the image of Nikki. Bianca explains to him that Videodrome killed her; the screen elongates into a weapon and shoots Max, effectively destroying his programming. Max is sent to kill the ones that desecrated his body, the abject people responsible for his unnatural transformation, crying out, “Death to Videodrome. Long live the New Flesh!” He is “the video word made flesh” as Bianca so eloquently puts it, a perfect synthesis of the organic and of the technological. When he kills Barry at the convention, he is effectively getting rid of the abject object responsible for his corruption; Barry explodes into a myriad of tumours, all trying to leave his body. As Kristeva declares in her book, “it is not the absence of cleanliness or of health that renders abject, but what disturbs an identity, a system, an order. What doesn’t respect the limits, the places, the rules?” Once Barry is eliminated, the last of the corruption needs to be destroyed; Nikki, imagined by Max, shows him that killing himself is the only way to end his mission and, under her guidance, he kills himself. Will he be reborn unto a higher state of being? The movie doesn’t answer, leaving the spectator to project his own personality, whether optimistic or pessimistic, on the possible ending of the film.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015