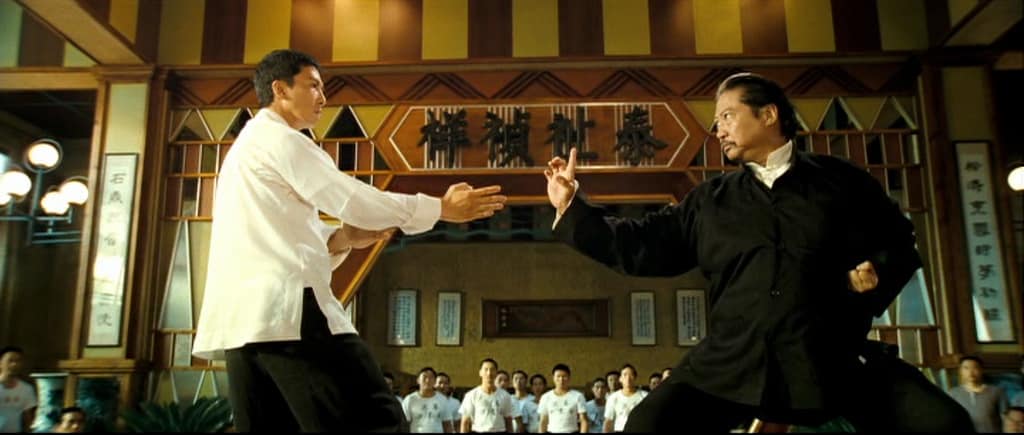

Ip Man 2 (Wilson Yip, 2010)

November 26, 2010

Sell Out! (Joon Han Yeo, 2008)

November 26, 2010One of the big draws in attending Fantasia for a cinephile is the emphasis on film history, especially when newly available restorations are shown. A few years ago, I had the pleasure of watching a newly restored 35mm print of the Shaw Bros. produced The Five Venoms (Chang Cheh, 1978), the best martial arts film I’ve ever seen. Kuroneko (Kaneto Shindo, 1968) is one of those gems, a ‘60s Japanese horror film with a sharp aesthetic.

Its static opening scene is quite striking. The movie slowly fades in on an idyllic country setting with a modest straw house to the left of the screen. To the right, walking from the far background, a team of rogue samurai, having probably escaped some battlefield, head inexorably towards the house. Once inside, after stealing any available food and water, they brutally beat, rape and murder the house’s occupants, a woman and her young daughter, before burning the house down and walking away with their loot. Angry at the circumstances of their deaths, vowing to pursue and exact bloody revenge if allowed to stay on Earth, the two women become ghosts, haunting a nearby forest, entrapping any samurai who dares to venture into their domain. Enter Gintoki, a young samurai hero who’s achieved success in battle, entrusted with the task of destroying the evil killing the elite warriors of his fief master, vowing to complete his task and become one of his master’s most trusted warriors. As soon as he encounters the ghosts, the samurai recognizes his fiancé and her mother, having left them ears ago to become a samurai. Both him and the ghosts are stuck in a dilemma: kill their loved one or renege on their respective oaths and lose their honor.

The interplay between the samurai and the ghosts is astonishingly suspenseful. The ghosts are never depicted as really human, from the obvious theater-like white make-up to the actors’ technique, but more as shadows of their former selves, which creates uneasiness, a palpable anxiety, during their interaction with the samurai. The mise-en-scene is beautifully theatrical, especially in the scenes inside the ghosts’ lair, taking great advantage of the beautiful shadows and depth of field. It’s all very stylized but totally believable and wholly integrated into the narrative. The ambiguous ending only serves to emphasize the impossible choice of the protagonists.

Dark, ambiguous, stylish, and inventive, Kuroneko incorporates well the style of ’60 Japanese cinema while treading further. Its treatment of the Japanese myth of ghosts is culturally, as well as historically, very significant.

More info on IMDB

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015