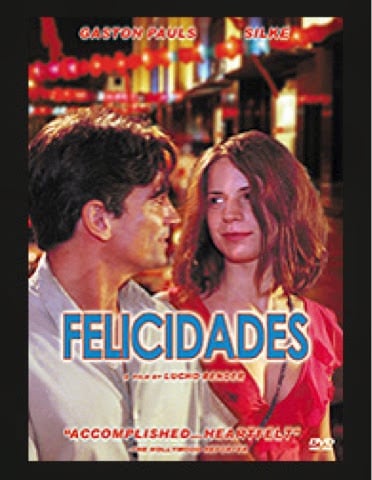

Felicidades (Lucho Bender, 2000)

March 26, 2010

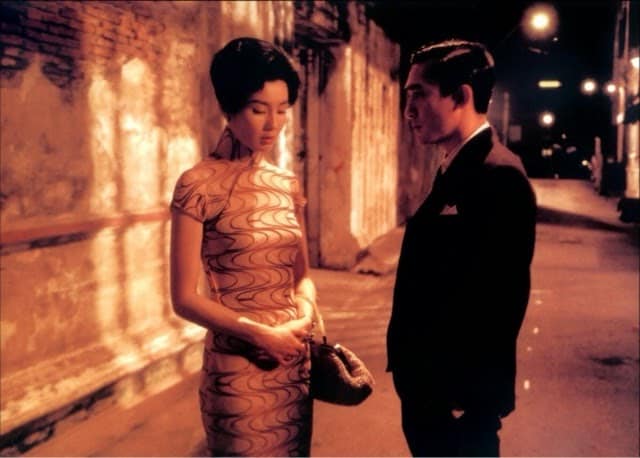

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

September 28, 2010What is also interesting with Flowers of Shanghaï formally is that, although HHH has decided for the purpose of the discourse on Old Shanghaï society, to aesthetically infuse a certain poetic atmosphere to the film, we can discern a great formal and stylistic continuity in relation to his other films like The Puppetmaster or Dust in the Wind. Ken Jones, talking about City of sadness, says in regard to Hou’s style: “Hou gets [the memorialization of spaces] by repeating the same composition again and again throughout the film, so that a given space often becomes as familiar and alive as the characters.” This constant style is certainly a part of Flowers of Shanghaï. As per usual, Hou doesn’t depend on camera movement to convey his story, choosing to depend on a more static — for lack of a better word — or a more subtle style. By a more conscious means of representation of space, Hou cues us instantly to which space we now inhabit and what story we must conjure to memory. The position of the camera in Crimson’s boudoir, for example, always shot from more or less the same positions, lets us mentally situate ourselves without the need for the institutional establishing shot. For each space, Hou defines an idealized filmic representation of it, one that’s easily — if not instantly — recognizable to the spectator, thus its familiarity. In his essay, Jones mentions the importance of the concept of liu-pai — a central concept in traditional Chinese painting to allow what is visible within the frame to open out into the mind of the viewer onto the world that extends beyond its parameters—to Hou’s films, a trait that also appears throughout Flowers of Shanghaï. In the most striking example of this, a drunk Master Wang, tired of waiting for Crimson, goes to look for her. As the camera stays in the room, we see him go into the corridor, looking left and right out of the frame, before going to the left until he’s out of the frame, though we still hear him going deeper into that undefined out-of-frame space. There is no more poignant example of a genuine desire from Hou to have us imagine that undefined space.

The sense of history that strikes the spectator when watching Flowers of Shanghaï is also common to his other movies. In The Puppetmaster, we discover the Japanese occupation in Taiwan through the eyes of Li Tien-lu, as he lived through it. In Flowers of Shanghaï, that sense of history lingers but we get a sense of a different kind of history, more of a social one than the politically charged Puppetmaster. Kent Jones adds (on City of darkness), “there’s a strong sense of accumulation. It’s not an accumulation of daily reality, as in De Sica, or an accumulation of time, as in Tarkovsky; it’s an accumulation of sensory perception”. And if Hou decides to accentuate our sensory perception by sexualizing our view, it can only serve the accumulation of history, the sense of immersion into Old Shanghaï. This desire is evident, for example, in the eating scenes, letting us into as much knowledge into the characters than into the period.

There is an evident consistent style running throughout the film, reminiscent of Hou’s earlier films but with a discernable desire to experiment with form. It works to the movie’s benefit.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015