What is independent cinema?

October 1, 2010

African cinema, Ousmane Sembene and the Western gaze

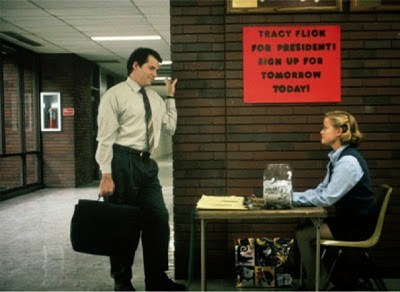

October 1, 2010I discovered Alexander Payne with Election. There are some movies that change your perception of what is possible, what is allowed. From time to time, you go to the theatre with no expectations and come out baffled by an object of pure beauty. Just like I was when I saw David Lynch’s Lost Highway, Robert Zemeckis’s Contact or P.T. Anderson’s Magnolia. Election was that for me.

The comedy genre is the most difficult of them all. I am astonished by the ease with which the French director Francis Veber creates laugh-out-loud comedies in L’Emmerdeur and Le Dîner de Cons. But the more I understand life, the more I realize that it’s never either tragic or comic but an amalgam of both. It is said that Aristotle, who gave us the book Poetics on which all drama and thus tragedy is based, had also written a volume on comedy which is lost forever (that tale is recalled and is a major plot points of In the Name of the Rose by Jean-Jacques Annaud). Some say that is one of the reasons we consider tragedy to be a higher form of art than comedy. With all this attention on tragedy, comedy is rarely reworked and its ambassadors, like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Louis de Funès, only considered great because of the undeniable power of their work.

This brings us to Alexander Payne’s oeuvre and Election in particular. As a dark comedy, Election is merciless, even sadistic in the way it mistreats Jim McAllister. It is conceivable that McAllister’s downfall is a tributary of his fixation on his student, who, seen through his eyes, looks like Satan’s spawn. We half expect her to grow horns and a pointed tail. But some things are not easily explainable. How do all the misfortunes that plague McAllister arrive at the same time? Are they all his doing? In About Schmidt, Warren Schmidt journeys through America, hoping to find meaning to his life following his wife’s death. His pitiful attempts and their unbearably shameful consequences are all Schmidt doing, as evident in the scene where he kisses the wife of a fellow traveller, confusing kindness for love (or lust?). But, in Election, an outside force seems at work, punishing McAllister for his thoughts, maybe sexual, maybe something else, toward the young Flick. Can it be Flick herself exerting that influence, like Damien, the son of the devil holding a shadow spear on top of his soon-to-be-dead adversaries in The Omen?

Election is a cautionary tale on the consequences of obsession. In the microcosm that represents the high school, common in all films of the genre, it is dangerous to go up against those that possess power, whether by birth or by acquisition. Flick is destined for greatness, whether McAllister accepts this fact or not. The ending, with McAllister throwing his drink at a senator’s car, further ingrains the inevitability of Flick’s destiny. It’s as if he were to try moving an immovable object. What is bound to happen will happen and the object will lie still. In that, the ending of Election is different than that of About Schmidt and Sideways. It persists in closing the story, giving it finality. We witness the extent of McAllister’s downfall, where his mistakes have taken him and the fates of all the other principal characters. In contrast, the endings in About Schmidt and Sideways are more ambiguous. In About Schmidt, Schmidt finds meaning in his life when he receives a letter informing him of how much his generous contributions have helped his sponsored African child. He bursts into tears and the movie end. I remember a lot of people in my theatre being surprised and frustrated at the sudden ending, but I’ve understood that, if the whole movie was about finding a reason to go on living, once that’s discovered, then the movie has no reason to be anymore. There was no need here for a drawn-out wrap-up showing us what would happen to Schmidt; his quest was over. Similarly, in Sideways, Miles finds meaning in his relationship with Maya; the movie ends when he goes to her, with a close-up of his hand on her door’s handle. It’s clear that he will open it, but maybe he won’t. Maybe he’ll chicken out, go back to his dirty apartment and sulk over how much his life sucks. He will then have become Harvey Pekar. There is also a point-of-view perspective in Election that is absent from the two others. In Election, the voice-overs shift point-of-view between all the principal characters, giving us an interesting perspective into their world, a narrative device absent from the two more recent films.

Payne’s work is a testament to miserabilism. In Election, McAllister loses all control over his life when he forgoes convention and develops a vendetta against one of his students. What happens to him is painful, somewhat justified but at the same time unjust since the aim of McAllister is only to protect the world from Flick’s ambition. A noble aim if, as he characterizes her, Flick is evil. However, Payne still leaves the door open to McAllister being wrong, that this romanticizing of his whole situation is an exaggeration of a mind warped by life’s hard struggles and by his own inadequacies. In About Schmidt, Schmidt is close to the same predicament, incapable of relating to what his life has become. His wife dead, his daughter about to marry an idiot and his best friend having revealed that he was his wife’s lover for years, Schmidt is left reeling through the whole movie from the realization that his life is meaningless. The ending, which I will talk about later, redeems him, putting his life into perspective. In Sideways, Miles Raymond is in the same pitiful position as Schmidt; his ex-wife, which he’s still in love with, is married to a better man, his novel isn’t that good, and he has no skills when it comes to women. Paul Giamatti’s role as an inadequate, bald man is reminiscent of his Harvey Pekar character in American Splendor without totally adhering to Pekar’s self-deprecation. Miles is socially inadequate, incapable of grasping the world around him, of making sense of it. He’s lost within it as he would be within a relentless storm.

Everyone has a group of principal influences that they carry with them always, and that they constantly refer to. Payne is one of those to me. The French filmmaker Patrice Leconte once said that he’s sad when he sees a bad movie because he can’t understand why someone would spend so much money on it, and he’s sad when he sees a good movie because he realizes he could never make that movie. Every time I see an Alexander Payne film, I hold on to my sadness because it can motivate me to create something beautiful.

Alexander Payne’s filmography on IMDB

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015