The World Of Apu (Satyajit Ray, 1959)

March 22, 2010

Araya (Margot Benacerraf, 1959)

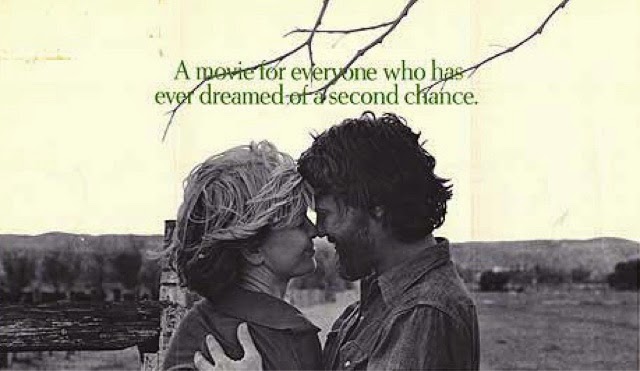

March 22, 2010I’m not a big Scorsese fan. Taxi Driver, for example, is highly overrated. In the 1970s, the gout-du-jour was amoral characters, from Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy to Cosmo Vitelli in The Killing of a Chinese bookie. It is a trait of the times that I don’t believe appeals to me at all. In Taxi Driver, Travis Bickle elevates cowardice to a high art. Hating in others what is blatantly obvious in him, he decides to blame everything and everyone for his misfortunes. He gives himself the role of the victim, and the film attempts to bring us to identify with his warped point of view. I don’t mind delving into the dark recesses of humanity but more the stand that Scorsese takes vis-à-vis his anti-hero. David Lynch’s cinema is one of perversion and ugliness, but somebody that would label it amoral would be missing the filmmaker’s point. That would be like reducing Cronenberg to horror. And, although, having seen The last temptation of Christ, I wouldn’t dare to reduce Scorsese’s work to gangster or dark films; I always felt that those were his preferred subjects. So it was to me a pleasant surprise to see Alice doesn’t live here anymore.

The opening scene is interesting in that it looked completely fabricated and plastic. The red horizon the little girl walked through gave the scene an ethereal-like quality that immediately made me think of two different fairy tale references: Alice in Wonderland, for obvious reasons, and The Wizard of Oz for the farm setting of the first scene. Scorsese will give us more references to the story’s basis in fairy tale. For example, to show us the house where Alice lives, he swoops down from the sky in a quick camera shot and stops in front of this ideal house, adorned with flowers.

However, more interesting is Scorsese’s intentional creation of a surreal atmosphere, from the swooping shots to the endless Elton John song (Doesn’t that song just go on forever?). Even when Alice auditions to get a job as a singer, the camera swoops several times around her, giving her performance a larger-than-life, unreal quality to it.

Is it a feminist film? Can a male filmmaker look at (and film) a woman through a female perspective? I don’t think so. If the movie is feminist, it is from a male perspective on feminist ideologies. The male characters are purposely caricatured, from the verbally abusive husband to the physically abusive psycho-boyfriend to the loud diner owner Mel and the beard heavy cowboy while the female characters all seem more developed. Both Ben and David are depicted as duplicitous predators, as they both instigate the relationship with Alice, even though she refuses their advances initially. It certainly puts her in a better victim mould when they both turn out after, in a revealing scene that always follows an initial sexual encounter, to be different men than presented. Alice is stuck in this patriarchal runaround where she has to dress sexy and look young to get a dead-end job, where she has to assert herself as an individual and not as being defined by her relationship to a man, where she has to take it all with a smile and try to raise a young man on her own.

Tommy and Audrey’s relationship is also important. It’s interesting to see Audrey, herself a future woman, drag Tommy into her subversion of the patriarchal order. In an additional example of the film’s adherence to feminist ideals, Tommy, who has been feminized, not only by his mother and the other women around him but now by Audrey, steals in opposition to the established patriarchal system, assuming her cause. When both children get caught stealing in a supermarket, their mothers come to bail them out but Tommy is the only one remorseful. By her attitude, demeanour and her appearance, Audrey appropriates the power men hold over women. She’s of the new generation, a woman unafraid of not adhering to convention, ready to put into question the order of things. She’s the essence of the film’s feminist inclination.

More info on IMDB

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015