Election (Alexander Payne, 1999)

October 1, 2010

The African diaspora: Colonialism and displacement

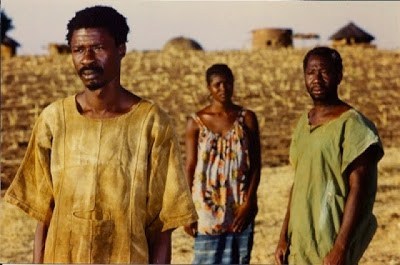

October 1, 2010Tilai and the burden of tradition in African cinema

Tilai (1990), from Burkinabe director Idrissa Ouedraogo, is the story of a shunned love affair between two young inhabitants of a Mossi village. Saga comes back to the village after a long absence to discover that his betrothed has, in the meanwhile, been married to his father. Unable to accept this fact, Saga decides to rebuild a straw house outside of town. However, his love for Nogma does not diminish and they both commit adultery, which forces them to seek happiness outside the village. What I feel compelling about Tilai is its criticism of tradition, insofar as it crushes individuality.

“Ouedraogo deals with society on the level of the individual and the small village,” declares Sharon Russell. On the village level, Ouedraogo shows the individual’s need for Family, as is the belief in Africa, is essential. Upon witnessing the village when he returns, Saga cannot help but smile before he sounds his horn. The reunion between him and his family are joyous up until the point he is informed of the nuptials between Nogma and his father. His father’s cold and brisk call for him to accept it does not help matters. So, Saga’s decision to live outside the village, as it is a desire to distance himself from the pain of his impossible love, is also a rebellion against society and its outdated and dehumanizing traditions. It is a more potent act when considered against the backdrop of African families, where an individual is only defined through the family structure. In Wend Kuuni (1982), from Burkinabe director Gaston Kabore, the mother of the title character is driven out of her village because she refuses to remarry after the death of her husband. She is ostracized, called a witch, blamed for the village’s woes and driven out to die in the wilderness with her child. In Yam Daabo (1986) from Ouedraogo, two children befriend an elderly woman, Sana, who is an outsider in the village. Since Sana is an orphan, she does not fit into this society “where family ties are of supreme importance”.

When driven out, as a consequence of his adultery and after faking his death, Saga seeks out the only family member that will not reject him, his aunt who lives in another village. He hasn’t seen her in a long while, as evident by the fact that she doesn’t even recognize him, but once she believes it is her nephew, she welcomes him wholeheartedly. Then joined by Nogma, they recreate their family in this new village. Only Saga’s obligation to his mother could disturb their bliss and precipitate the story’s tragic ending. When he learns his mother is on her deathbed, Saga breaks his promise to his brother never to come back and ventures to the village to say goodbye. His reappearance forces his brother’s hand. Tugged between his loyalty to his father and his brother, Kougri had left Saga alive. When Saga shows up, his father understands Kougri’s betrayal and banishes him. Faced with the loss of his family and village existence, Kougri shoots his brother before walking away from the village. Saga dies in his mother’s arms, where he came into his world.

But, although societal rules lead to Tilai’s tragic ending, it is the eulogy to individuality and change that infer the most meaning to the film. Saga, and Nogma are transgressors, the first by living away from his family, the second from disobeying her father’s decrees, which will lead to his suicide. They both consume their love and fall into adultery, fully aware of the implications of their act and under the watchful eye of Kuiga, Nogma’s younger sister. Nogma will later leave her village and her husband to be with her lover. Kuiga will continue the rebellion as she arrogantly talks to her father in another scene. As Sharon Russell explains:

“The tragic end of the story is a profound illustration of the effects of strict adherence to the rules of a social order. The film does not condemn the simple life of the village, just its resistance to change. The agents of change are the young people who cannot understand why unreasonable laws should be obeyed”.

And, even though the transgressions lead to the Saga’s tragic end the ambiguous ending, where Nogma and Saga’s aunt walk towards the village, could infer that even though in this case change has resulted in tragedy, it is essential for the evolution of the Mossi people.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015