Election (Alexander Payne, 1999)

October 1, 2010

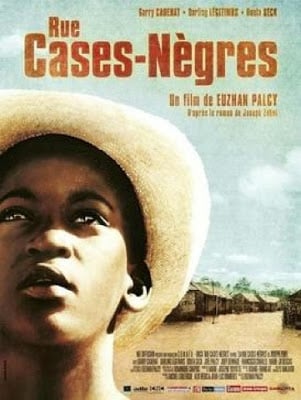

The African diaspora: Colonialism and displacement

October 1, 2010Emitaï and the ineffective passive resistance

Emitaï (1971) starts with beautiful shots of the natural African landscape and a young Diola villager, the same tribe we will follow during this story, is informed that the French Army has requested young men from every village to recruit for the war in Europe. Under duress, the young man accepts and is taken away as his family looks on. When one year later, the soldiers come back requesting a rice tax decreed under Pétain’s orders, the French head of state. Rice being sacred to the Diola, the village takes a stand against the invaders when the women hide the rice to keep it from the soldiers. Sembene says he based his story on a real village, which gives the narrative a bigger impact:

“[The village] is a Senegalese village which was destroyed by the colonial army, but which still exists. We keep these villages like relics of our history. I was relatively young in 1942, not yet in the Army, when the Diola massacre took place.”

The French and the British were cruel colonizers, having to be forced out of almost all of their colonies that strived for independence. For Sembene, “the struggle in Emitaï is an anti-colonial struggle”. Here, the French Army’s cruelty is demonstrated by their concurrent actions and interference in the villagers’ lives. First, by abducting their sons, the colonial power comes in direct conflict with the natural order of succession of the village. If the sons die in the war, an event far removed from the Diolas reality, there will be no men left to continue the village’s traditions. From the point where the young men are drafted, the only masculine presence left in the village is the old men. This has special significance for the African villagers for whom family is of the utmost importance.

Even after this event, the colonists further humiliate the villagers by their demands for rice, which is not only important for their sustenance, but has religious and social significance. After the village refuses to comply, the soldiers torture the women by placing them in the sun until they give up the rice. When the elders finally give into the soldiers’ demands, they are further humiliated by being forced to carry the rice to the Army headquarters. On the way, in the movie’s poignant ending, the villagers decide to resist and are massacred for it. For Sembene, the French have always been merciless colonizers, no matter who gave the orders:

“For us who were the colonized, Pétain and De Gaulle were the same thing, even if young people today know there is a difference between them. The story of the soldiers killed in Senegal; the story in Algeria in 1945 is De Gaulle; the story of Madagascar is De Gaulle; why do people want De Gaulle presented as a hero or a superhero?”

In the movie, the two French leaders are interchangeable; in a comedic scene where the director appears, the African soldiers in the French Army are asked to take down all the posters of Marshall Pétain and replace them with ones of De Gaulle. But, as they discuss the change in the regime, they can’t seem to distinguish perceive any difference between the two.

In Emitaï, by showing the Diola resistance, Sembene’s film also echoes Guinea-Bissau’s fight for independence. Guinea-Bissau, immediately south of Senegal, was the scene of a major armed liberation struggle against Portugal, which it had belonged to for centuries. This struggle, under Amilcar Cabral, ended in victory in 1975 for the natives. Their plight fuels the film’s narrative. Sembene continues:

“[…] The story of Emitai takes place then in a Diola village, next to Guinea-Bissau. The same tribe lives in the south of Senegal and the west of Guinea-Bissau.

While the film was being shot, some extras came from Guinea-Bissau, and the fighters and the resistance people of the time helped us a lot. At the film’s premiere in Casamance, President Cabral came to see the film with some fighters; as people were leaving, they all came to tell us that the film had been made for them, and not just for other people, because it was the same struggle”.

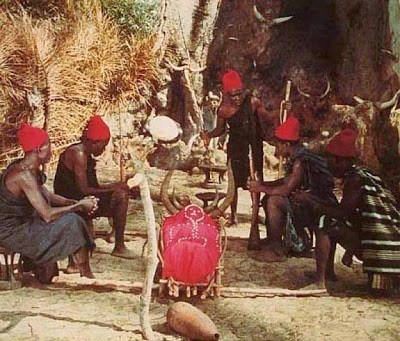

Sembene has, in Emitaï, a Marxist view of religion, in that it renders the villagers passive in their resistance to foreign incursions. Faced with the loss of their harvest, the elders turn to debating and to their animist gods. But while they discuss the issue, their women and children are being tortured by the soldiers who force them to sit under the sun. In truth, it is the women who show a revolutionary side, first by hiding the rice, then by their solidarity against the French Army. By privileging the action of the women, and showing the inefficacy of the men’s resort to their gods, Sembene is critical of this peaceful resistance:

“The gods never prevented colonialism from establishing itself; they strengthened us for inner resistance but not for an armed resistance. When the enemy is right there, he has to be fought with weapons”.

Emitaï is a heart-wrenching depiction of the nature of colonialism and the contemporary plight of the Third World, what Noureddine Ghali calls “the hidden face of colonialism”.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015