Election (Alexander Payne, 1999)

October 1, 2010

The African diaspora: Colonialism and displacement

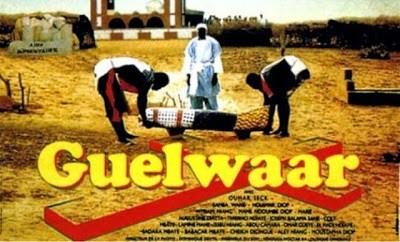

October 1, 2010I was introduced to African cinema during my studies at Concordia University when, in a film history class, I was touched by one of the most poignant, engaging, and thought-provoking works I had ever witnessed. With Guelwaar, my perspective changed, not only as what type of filmmaker I wanted to be, but also what kind of man I needed to be.

That’s the impact, for me, of African cinema in general, and Ousmane Sembene’s work in particular. In its different perspectives and traditions, it draws the spectator into its narrative, nurturing a symbiotic relationship with life itself. In that sense, it’s cathartic. I’ve been privileged to view several of these life-affirming films. This article relates my experience of each viewing.

Guelwaar, or else the gears of Neocolonialism

Guelwaar (1992) is the story of a political man who rises as the conscience of the Senegalese people and is silenced by the acting political figures for his transgression. To further humiliate their political opponent, Guelwaar’s body is swapped for another man’s and is buried in a Muslim cemetery—Guelwaar, or Pierre Henri Thioune, is of Christian faith—where his spirit will never be allowed to rest. This leads to a confrontation between Guelwaar’s family and the Muslim family. Here, Sembene delves into territory visited before in Ceddo (1977), the interference of religion in Senegalese life, although from a different standpoint.

In Ceddo, the incursion of Islam into Senegalese territories disassociates the natives from their heritage, from matriarchal traditions to the exclusion of the Ceddo, “the defenders of traditional cultural identity”. The advancement of Islam is portrayed as imperialistic, forced upon the people by their king and his new imam. In one scene, where Islam is imposed on a whole village, Sembene appears as one of the villagers, an ideological decision from the director positioning him as one of them. In Ceddo, the incursion can only be stopped by the Senegalese people, here identified to the Princess Dior, and with massive and immediate action. When Princess Dior shoots her father’s imam’s genitals with a rifle, it resolves the narrative’s conflict, and although we know that the problem couldn’t have been easily resolved historically, it supercharges the audience ideologically.

In Guelwaar, the religious polemic is of another nature. Islam and Christianity, two foreign religions, have polarized the Senegalese into two opposite camps. The folly of the affair becomes evident in the confrontation scene between the two families. When an officer and a local representative get involved in settling the dispute, not unlike the communal village depicted in movies like Wend Kuuni (1982), both camps come to the realization that an understanding is better than confrontation. Where religion has pitted brother against brother, Sembene shows that the Senegalese’s nationalist bonds are stronger than makeshift, religious ones. And by enunciating these divisions, Sembene sheds light here, albeit indirectly, on the social classes, the gender distinctions, the neocolonialist influence and their attack on homegrown culture.

Guelwaar is a scathing critique of neocolonialist politics and foreign aid to the Third-World. To me, that aspect of the narrative takes predominance over the religious in-fighting and enunciations of Senegalese bureaucracy. Sheila Petty agrees: “What predominates, however, is Sembene’s critique of foreign aid, which, according to Françoise Pfaff, was later grafted onto the story of the burial mistake.”When the story starts, Guelwaar has already been murdered and his family prepare for the funeral. It is only later that we are allowed to view the scathing scene that warranted Guelwaar’s death. Atop the podium, in a eulogy for the foreign aid just awarded to the Senegalese government, in front of imperialist dignitaries and corrupt politicians, Guelwaar denounces the handouts, calling for the Senegalese to break the bonds of neocolonialism and free themselves of the slavery of foreign aid. He declares:

“Famine, drought and poverty, do you know why they happen? If a country is always taking aid from another country, that country will always only be able to say one thing … thank you, thank you, thank you.”

Guelwaar enunciates his position after his daughter Sophie is revealed as a prostitute. He states:

“I’d rather she were a prostitute than a beggar … rather she was dead than a beggar.”

Later, he continues:

“Woe betide the one who holds out his hand and waits for others to feed him and his family.”

The last scene with the children spilling bags of foreign aid on the ground is powerful, chiefly for the taboo that it entails—in countries where food is scarce, whatever quantity there is precious, for another because of the drastic position it takes and demands us to take. To Sembene, dignity is more important than comfort, more important than life. He separates the capitalist imperative from the Senegalese lifestyle, where family is of more importance than wealth. And, in our global climate, that is the truly revolutionary idea.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015