Flowers of Shanghaï (Hsiao-Hsien Hou, 1998)

September 28, 2010

Cronenberg’s discourse through Videodrome and eXistenZ

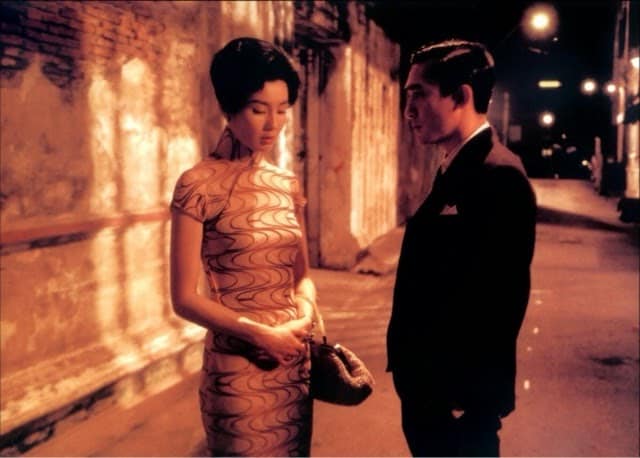

September 28, 2010Director Wong Kar-Wai is considered an influential filmmaker. His style and vision, which borrows from art-house directors such as Bresson and Godard, is thoughtful and modern. His films have been acclaimed by international critics for their emotional effect and stylistic value. In the Mood for Love (2000) was a big commercial success for him. How does it compare to Wong Kar-Wai’s other work? How does it fit into his filmography? Is there a need to talk of a dream-like imagery throughout the film? How does it manifest itself?

For me, the most memorable element of In the Mood for Love is its emotional charge. The film’s English title is more representative of its content and atmosphere than its Chinese title, Huayang Nianhua (which means “Full Bloom” but is more accurately translated to “those wonderful varied years”). If Full Bloom is a title suited to the tradition of melodrama, which In the Mood for Love pays homage to, and Those Wonderful Varied Years is a controlled evocation of nostalgia, the English title immediately sets up the atmosphere that the film will adopt. It’s very close to the conception that Stanley Kubrick has of filmmaking:

For me, the most memorable element of In the Mood for Love is its emotional charge. The film’s English title is more representative of its content and atmosphere than its Chinese title, Huayang Nianhua (which means “Full Bloom” but is more accurately translated to “those wonderful varied years”). If Full Bloom is a title suited to the tradition of melodrama, which In the Mood for Love pays homage to, and Those Wonderful Varied Years is a controlled evocation of nostalgia, the English title immediately sets up the atmosphere that the film will adopt.

“A film is—or should be—more like music than like fiction. It should be a progression of moods and feelings. The theme, what’s behind the emotion, the meaning, all that comes later.”

Stanley Kubrick

This quote could be used to describe In the Mood for Love, as the intent of Wong Kar-Wai was to communicate a mood or feeling and not necessarily a narrative. It is towards that ultimate objective that the director will use slow motion, repetition and a doubling effect.

Slow motion is used to enhance this ethereal feeling that Wong Kar-Wai wants to convey. Those scenes are all linked together by a narrative thread: they always involve the two protagonists, Mrs. Chan and M. Chow, and emphasize their connection to one another. In the first of those scenes, Mrs. Chan, sitting next to her husband, is gently shoved aside by Mrs. Chow (by a very dry hand gesture) who goes through her to sit as M. Chow leaves the table. But, in a brief moment, as M. Chow and Mrs. Chan’s eyes meet, a rapport is established, whether they’ve realized it or not, that Wong Kar-Wai chooses to suggest visually by this dilatation of time. After picking up some noodles at the market, Mrs. Chan will leave a few instants before M. Chow arrives, signifying, at this point in the story, the distance between the two characters while emphasizing, with the slow motion, the affinities they share. The second time, they will meet on the stairs to the market and smile to each other, getting closer with each encounter. After meeting in an American-style diner, there is a slow motion shot of them walking through a Hong Kong street; we see them from behind as they seem to finally be a couple, their closeness emphasized by the slow motion.

“Central to Wong Kar-Wai’s work, critics agree, is the theme of time. It appears in many guises—the mysteries of change, the ephemerality of the present, the secret affinities among simultaneous incidents, the longings created by memory and nostalgia.”

David Bordwell

It’s this mystery of change, these affinities among incidents that bring the two characters closer together. However, in this street shot, and the one that follows it, the first simulation (see below), Wong Kar-Wai brings ambiguity to their relationship. We will often ask ourselves throughout the movie: are they themselves or are they their spouses? Is this real or another simulation? This unclear approximate state will enhance the sentiment and the atmosphere built. The lyrical music that accompanies those slow motion scenes adds to their dream-like character, but through its use, Wong Kar-Wai brings into play the second element contributing to this ephemeral mood: repetition.

A scheme of repetition runs through In the Mood for Love. Wong Kar-Wai repeats situations, bits of dialogue and shots in order to amplify the film’s mood as well as craft his discourse. There are two kinds of repetitions used in the movie, those with variation and those without. In the first ones, the repetition emphasizes the variation; in the second, the repetition itself is called to attention. The market scenes, are an example of the repetition that structures the film. Every encounter of M. Chow and Mrs. Chan at the market is almost exclusively filmed in the same manner, as to highlight their growing connection. The diner scene will adhere to this practice and will be seen twice. In the first one, M. Chow and Mrs. Chan come to the realization hat their spouses are having an affair with each other, with Nat King Cole’s Spanish-language song, Aquellos Ojos Verdes, playing in the background. In the repeated scene, the two of them talk about their spouses, trying to simulate a dinner they would’ve had together, with the same Nat King Cole song playing. In one of the taxi scene, M. Chow tries to hold her hand, but she pulls back.

When the taxi scene repeats itself, after M. Chow has confessed his love for Mrs. Chan, she is the one this time to grab his hand and hold it. In a soft voice, she declares, “I don’t want to go home tonight,” letting him know that she feels the same way about him. Later, the two of them repeat the same off-frame dialogue (“It’s me. If there was a second ticket, would we be leaving together?), always following a scene where one of them, conflicted about their relationship, has been watching himself/herself through a mirror.

All those scenes show either a regression of the characters, as in the diner scene, a way for them to give meaning and logic to a situation or an emotion that has none, or a progression, as in the taxi scene, towards a better understanding of themselves. The final scene follows the logic of repetition but of a narrative one. Mr. Chow tells his friend that their ancestors secrets always stayed hidden because they use to go to the forest speak their secrets to a hole in the trees and seal it, ensuring that their secret would remain buried. When he himself visits the ruins of Angkor Wat, he speaks to a hole in the wall something that is hidden from us, and once he leaves, the hole is sealed by dirt; his secret love affair will forever be concealed from everyone, us included. The sudden appearance of that scene’s lyrical musical piece, only used at that time in the movie, breaks the pattern of repetition that has, up until now, inundated the movie. In that moment, M. Chow is a changed man, free of the patterns of obsession, of his past and free to look to the future, as shown in the shot of him leaving the ruins.

There are numerous repetitions of shots throughout the movie. The slow motion shot where everyone is at the dining room table at the beginning of the movie repeats itself later in the film with a counter-shot of M.Chow at his new newspaper job. They seem to think of each other, the slow motion, as was said earlier, emphasizing their connection with one another. M. Chow’s wife is also given presence by the repetition of the shot of a window at her place of employment; by association, every time we see the window and hear her voice, we immediately know it’s her. In that regard, the repetition serves as an aid for the film’s reading. After volunteering to walk home so as to not arise any suspicion or gossip, M. Chow is surprised by a sudden occurrence of rain. He is shot in a decrepit alley, leaning against the wall, waiting for the rain to stop. The next shot is the same one but the next morning, with Ah Ping, M. Chow’s friend, hurrying to bring him some medicine. That shot will be repeated several times but most notably when M. Chow and Mrs. Chan will both be trapped by rain in the street, showing the progression of their relationship. Several narrative elements are accentuated by repetition. The use of clocks throughout the story points to the passing of time as an unstoppable nostalgia machine. If there is no way to stop time, then what has transpired can only be remembered and no longer experienced. Memory becomes therefore a human necessity to the passing of time, with nostalgia as its by-product. Music is repetitive, especially the movie’s lyrical theme which is constantly repeated but is never played in its entirety, triggering a feeling of familiarity and thus nostalgia of the spectator towards the musical score. Rain, often used in the film, evokes melancholy, an emotion which impact is close to that of nostalgia. The use of doubles in the elaboration of the story and the mise en scène solidify the mood of the film.

Jean Baudrillard, in his famous book, Simulacra and Simulation, says that “the double is the quintessential prototype of the simulacrum”. In the Mood for Love is a perfect simulacrum of melodramatic film and romantic film. The idea of the double is continuously exploited throughout the film. At first glance, we notice the names of the two principal characters, Chow and Chan, which are closely related. Does that mean that M. Chow and Mrs. Chan are doubles of each other? Several clues would seem to suggest it. In one scene, M. Chow talks to an out-of-frame M. Chan about his wife and later, Mrs. Chan does the same with Mrs. Chow. Both scenes are filmed as to deny us any point of reference for the spouses, to give them an abstract presence, interchangeable and purely symbolic. Several scenes will place them as mirror images of each other through an imaginary axis of refraction. After being caught in the rain at the market, they come home and, at the same time, enter their apartments. For a brief moment, it’s as if they’re looking at themselves by looking at each other. Later, after the second taxi scene, both lean on the walls of their respective apartments, in symmetrical vis-à-vis of one another. This device used by Wong Kar-Wai is echoed in the many shots of mirrors in the movie.

If they are doubles, some scenes suggest that they are doubles of their spouses. In all their scenes of simulation, they seem to conjure up the presence of those abstract presences that we are never allowed to see. In their first simulation, in the first diner scene, they try to imagine how their spouses first encounter went, pretending to be them. Their simulation may prove to be the reality, their imagination having copied perfectly what happened. But it is, to the spectator, the only reality since it is the only possible scenario that is given to us. Both protagonists go on to simulate their first encounter, trying to put the blame of the first move on each other’s spouses and therefore, by cause of the doubling effect, on each other. Their doubling is so absolute that we will mistakenly perceive them as their spouses in some scenes until they are revealed to us, for example, when Mrs. Chow practises asking her husband about his affair. In that scene, as long as M. Chow is hidden, he has the potential to be M. Chan until he is revealed to us. Both characters are thus interchangeable with their counterparts, contributing to the film’s abstract and unclear mood. If Wong Kar-Wai’s work has in the past been somewhat different than In the Mood for Love, the film retains the director’s thematic and stylistic elegance. An oeuvre of pure emotion, the film conveys Wong Kar-Wai’s vision with impressive clarity and efficiency. Wong communicates his feeling of ethereality by his use of slow motion, repetition and the doubling effect, which amplify the ephemeral quality of the film. In that regard, Wong Kar-Wai has a lot in common with Stanley Kubrick, who believed that moods were the driving force of a movie. Wong decided, for this movie, to scout for locations he liked and write scenes around them. With that method, space takes on a great presence, as seen in the solemn feeling of the Angkor Wat ruins that closes the movie. In the Mood for Love appears to be the director’s strongest film.

Bibliography

BAUDRILLARD, J.: Simulacres et simulations, Galilée, 1981.

BORDWELL, D.: Avant-Pop Cinema, in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachussets, 2000, pp.261-281, notes, pp.317-319.

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015