Woochi (Dong-hoon Choi, 2009)

November 28, 2010

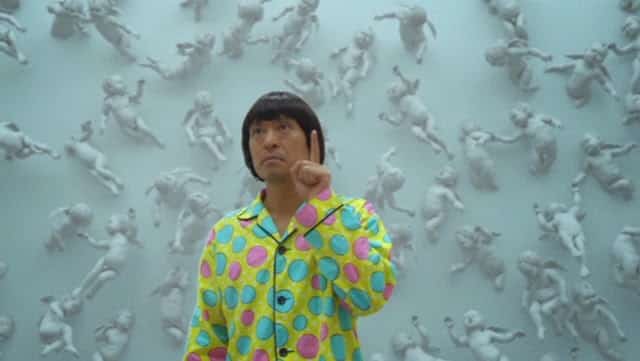

Symbol (Hitoshi Matsumoto, 2009)

November 28, 2010It’s a fine line between social change filmmaking and propaganda. Ousmane Sembene films, for example like Ceddo (1977) about the colonial spread of Islam and Christianity through Africa, Guelwaar (1992) on foreign aid to third-World countries and the impact of imperialism, and Moolade (2004) about the traditional excision of young women, are ideological in form and content, owing much to Sembene’s film training in Russia, but still display a strong interest in education rather than indoctrination, in public interest topics rather than political ideology.

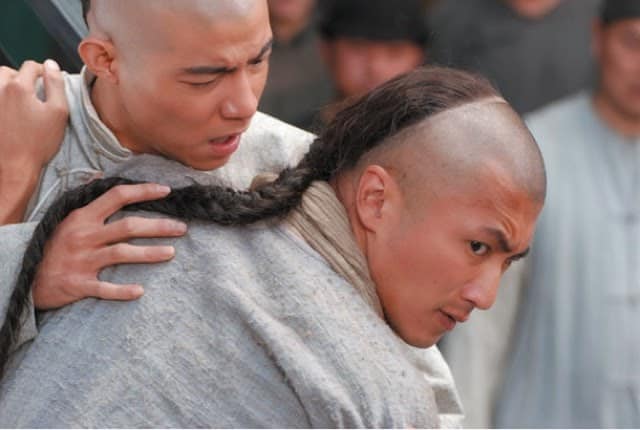

Teddy Chan’s Bodyguards and Assassins (2009), a remake of Taiwanese film Chi dan hao han (Tung-min Chen, 1974) is the story of Dr. Sun, a Chinese revolutionary, en route to visit Hong Kong to unify the resistance against the Chinese emperor of the last Qing dynasty, of the patriots who pledge their lives to safeguard Dr. Sun’s and of the assassins sent to the island to make sure Sun never accomplishes his goals. The movie also delves with some skill into the lives of its characters (political activists, young martyrs, noble families) but only to give the ending just enough pathos. In the events leading to the historic day of October 15, 1905, the revolutionaries are on their own, caught between a corrupt mainland, indifferent British colonists and an army of trained assassins. It’s a perspective that has been running around, through this past decade’s Chinese and Hong Kong films like Purple Butterfly (Ye Lou, 2003) and Ip Man1 and 2 (Wilson Yip, 2008; 2010), depicting ideological figures without the subtlety and complexity of real events. Film reader Andy Willis, citing scholars William Davis and Emilie Yeh in his article Hong Kong Cinema since 1997, published in Film Int (issue 40, volume 7, number 4, 2009) talks about the influence of the mainland on Hong Kong’s new slate of films since the handoff:

“The result is diluted, with producers aiming at external marketing over internal quality […].”

The economic advantages with a closer business connection with the mainland are obvious: bigger budgets for bigger box-office returns. However, the perverse effect on quality and creativity in the final products is as perceptible as in Hollywood filmmaking, leaving Hong Kong’s previous markets to look to its independent films for artistically relevant content. Andy Willis states:

“It is within the arena of smaller budget films that an identifiable Hong Kong cinema continues to struggle to assert itself.”

An enjoyable blockbuster co-produced between China and Hong Kong with an estimated budget of 23 million, brimming with magnificent Chinese stars like Donnie Yen, Xueqi Wang and Tony Leung Ka-fai Bodyguard and Assassins tugs at the heartstrings, with its use of slow motion and close-ups for dramatic effect, building to a martial arts confrontation where the goal is never for our heroes to survive. Like in Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002), the protagonists’ sacrifice is essential for the creation of a new nation, free from oppression and dictatorship. An idea that, in itself, isn’t wrong but the use of film as a tool for political recruitment or ideological propaganda, for a subjective rather than universal agenda, like Hollywood does, is misguided and ill-advised.

More info on IMDB

- Black Panther: A Perspective - March 20, 2018

- Seven Pounds (Gabriele Muccino, 2008) - May 5, 2015

- Honeymoon (Leigh Janiak, 2014) - January 30, 2015